The music business has been screwed up for a hopelessly long time, but change is afoot: Congress, courts and the Justice Department are all poised in coming months to shake up how companies and consumers pay for music. The big question, though, is whether this flurry of activity will produce a rational royalty system — or just make the existing rathole even deeper.

Here’s what to watch for in a year that could change the rules of the game for performers, Pandora and everyone else with a stake in music.

The last month has seen the return of two proposed bills in Congress. One is the Local Radio Freedom Act, which would ensure that traditional AM/FM stations don’t have to start paying performance royalties on top of the songwriter fees they currently pay. The other is called the Songwriter Equity Act, which would tweak the way so-called “rate courts” calculate how much people who write songs should get paid.

Both bills have appeared before in one guise or another, but never passed. This time, the outcome will be determined in part by whether Congress takes up the issues at stake on its own, or as part of a larger royalty reform effort.

Meanwhile, industry attention is turning to the Justice Department, which is holding a hearing on March 10 over so-called consent decrees. These are antitrust orders that apply to ASCAP and BMI, two giant outfits that license songs on behalf of music publishers, and require them to license song rights at a fixed price to all comers. The antitrust orders have been to a boon to everyone from cover bands to bars to radio stations because they provide an easy, efficient way to clear copyrights. But music publishers say they are getting short-changed and want the orders, which date from the 1940’s, to be changed or abolished outright.

Finally, some high stakes court cases increase the chances this will be a year of reckoning for the music industry.

Digital on trial

The most contentious of these cases involve an aggressive series of class action lawsuits, brought by record labels and former members of the band The Turtles. In courts from California to New York to Florida, the labels are claiming that Pandora, Sirius-XM and other digital music services have failed to pay for performances that date from prior to 1972.

The legal theory appears far-fetched, but it’s gained traction before some judges. If the cases go any further, they will have huge financial and legal implications not just for Pandora, but for any other service that plays old music on the internet. (The labels also pushed the issue last year through a proposed law, The Respect Act; look for that bill to return if the labels strike out in court).

And, if all that’s not enough to keep track of, there’s also a court clash between Pandora and BMI. This one is about royalty rates, but also about whether publishers who use BMI to license their songs can pull the digital portion of their catalogues or if they must instead be, in the words of one judge, “all in or all out.”

A ruling in favor of BMI could cripple digital radio services, but that appears unlikely given that ASCAP lost a similar case last year.

What the fight’s really all about

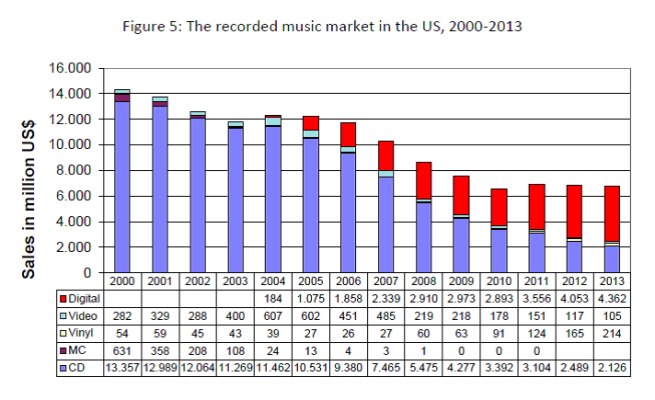

All of these disputes are bitter and complicated, but the source of them can be summed up in a sentence: the music royalty pie has shrunk significantly, and what’s left of it is being distributed unequally. As an RIAA report in 2013 revealed, digital sales may be growing, but not fast enough to offset the long-term loss of CD sales. Professor Peter Tschmuck, as part of an analysis of the U.S. music industry, put the RIAA’s data into a chart last year:

These larger forces are why many of the measures now floating around — the songwriter law, the consent decrees, the court cases — won’t do much to change the game. Such piecemeal fixes also do little to acknowledge the current royalty system is broken because it’s built on assumptions of the analog era.

The proper way to approach the problem is instead to require the music industry to recalibrate the entire copyright collection process from the ground up and, especially, to fix two major imbalances in how money is collected and paid. The first imbalance involves a seemingly irrational distinction in how the law treats AM/FM stations and digital radio.

Pandora, for instance, is a favorite punching bag of the industry, but the company also spends the bulk of its revenue paying performers — even as traditional radio stations pay nothing at all. The reason for this, Washington insiders suggest, is that members of Congress are eager to make nice with local stations on which they rely heavily during election campaigns. This is why they are happy to let them pay nothing to performers, while at the same time throwing the likes of Pandora and Sirius-XM under the bus when it comes to royalty rates. But for musicians and for consumers, there’s really no reason why digital and AM/FM should be treated so differently.

The other big imbalance when it comes to royalties is between songwriters and performers. Many people will be surprised to know that when performers do get paid, which is the case when a song is played on digital radio, the rates can be up to ten times higher than what the songwriters (and their publishers) get.

The reason for the imbalance in this case, though, is the consent decrees that set the rates at which publishers get paid. The Justice Department could address this by lifting the decrees, and allowing publishers through ASCAP and BMI to charge what they like. But this could lead songwriter rates to go through the roof, and fatally wound digital radio services once and for all (recall Pandora is already on the ropes). It would also create new licensing headaches for restaurants, bars and other places that play music.

That’s why any solution that looks to pay songwriters more will also have to consider when it is appropriate to pay record labels, which represent the performers, less.

As for the dispute over pre-1972 recordings, the court cases (and the now-dormant Respect Act) appear to be no more than a cash grab through copyright expansion. Judges and law-makers should blanche at the idea of handing out windfalls, at the expense of consumers, for music that is already 50 years old. Such a gift would be a boondoggle akin to ethanol subsidies or the Bridge to Nowhere.

Change is coming.. but for better or worse?

All of this comes at a time when musicians are having a harder time than ever. The record industry that once nurtured them has shrunk dramatically, CD sales are drying up rapidly, and internet royalties are not making up the difference. But on the bright side, the internet has introduced new efficiencies that make it easier to track song sales and distribute payments (which helps explain ASCAP’s surprising $1 billion year.)

A solution from courts or Congress is in order. The danger, though, is that a partial solution will protect parochial interests such as FM stations or labels that own 1960’s recordings without creating a sustainable system for royalties in the digital age. There’s also a risk that changes to the law will simply scapegoat companies like Pandora and Spotify, which represent the future of music, or even kill them off altogether.

In any event, watch closely. This is the year that a lot of long-time log-jams in the music industry appear set to move.